-

-

Improve Your Observations by Asking Better Questions

So acquire the habit of being present at this activity of the material and moral universe. Learn to look; compare what is before you with familiar or secret ideas. Do not see in a town merely houses, but human life and history.

If you cannot look thus, you will become, or be, a man of only commonplace mind. A thinker is like a filter, in which truths as they pass through leave their best substance behind.

– Sertillanges

Imagine with me for a moment, that we are members of a team of researchers tasked with traveling through time to collect first hand anthropological research on ancient cultures. However, on our latest assignment the time machine malfunctions. We crash land in an unknown time and location. We are confused and directionless.

This is how thinking and learning often feels. We know that the pursuit of knowledge, and the thinking that follows should begin with inquiry (research). But the landscape of that research is often vast,confusing, and directionless. Like our hypothetical team of time-travelers, we have a hard time figuring out where we are, when we are, and what we need to know in order to get back home.

In this post, I want to propose that successful navigation through the ambiguous terrain of inquiry depends on our ability to make good observations. The quality of those observations is directly related to the quality of the questions we ask in the research process. Below, I elaborate on this important relationship, and provide the three step guide I use when formulating my own research questions.

Thanks for reading Cognitive Craftsmanship! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.Subscribed

Observations Start With Questions

In a previous post, I described observation as the foundational skill we need in thinking and learning. Observation is the skill of noticing. It is the distinct act of calling something to attention and of moving information from the background into the foreground. When you highlight a sentence in a book or write something down that you heard in a lecture, you are making an observation. You are making an intentional choice to call something out from the background of the page or speech, and put it into the foreground of your notebook.

For our team of stranded time-travelers, they will need to make excellent observations using some of the expertise and training they have (memory), to map out where and when the time machine has crash landed. The quality of their observations will directly depend on the quality of the questions they ask. For example:

- Low Quality Question: What time period are we in?

- High Quality Question: What can the building materials/methods of the civilization tell me about this time period?

Crafting good research questions is a lot like making a map. We embark on the turbulent journey of research because there are things that we want to know. When we set out on the journey to find the answers, we collect observations (data). Those observations are then collected, organized (taxonomy), and stored (memory). From there, they can be called upon in order to form conclusions and solutions.

In the pursuit of excellent thinking, the observations we collect are directly related to the questions we ask. Often, when research feels confusing and directionless, it is a result of having not asked the right questions. Asking good research questions is a craft and the most important part of the research journey. After all, one should not set out on an expedition without a good map.

Making A Map With Questions

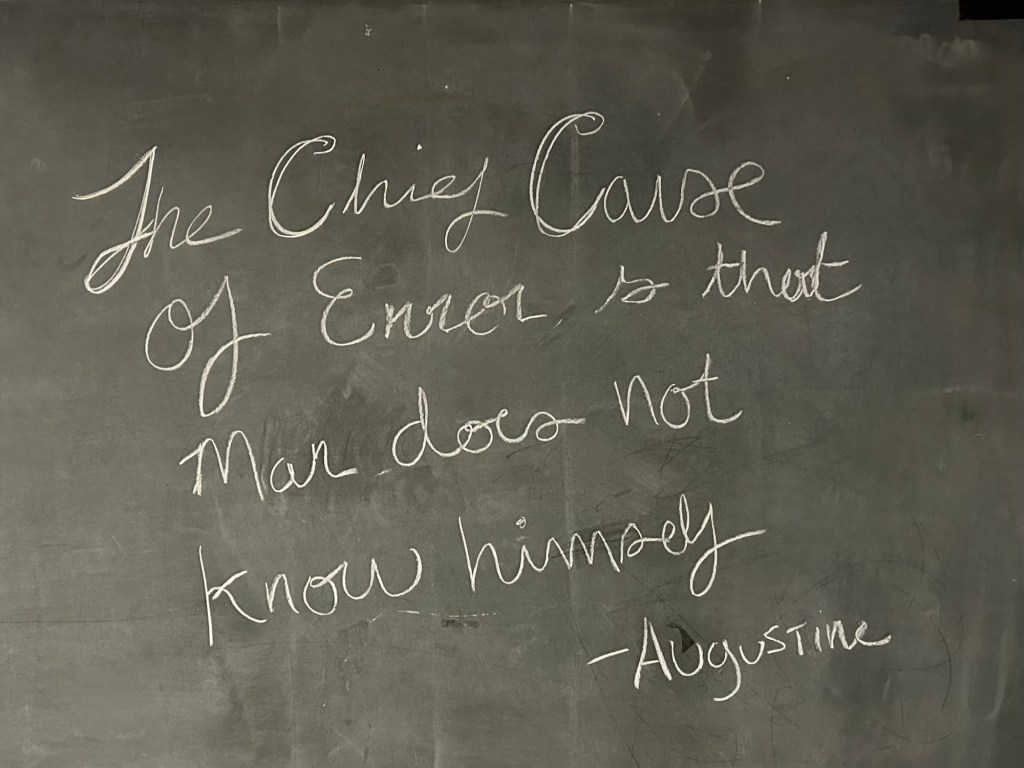

Step 1: Make a Pirate Map

By “Pirate Map,” I am simply referring to the silly cartoon maps we were familiar with as children. They feature big dotted lines, an “X” that marks the spot, and general directions based on landmarks (e.g. you will know you’re close to the treasure after you pass the mountains).

When we start our research journey we need a similar approach. We need to know what the big landmarks are that we are looking for. I often refer to this as the “research domain.” If I find myself in a domain that doesn’t have the big landmarks, then I’ve drifted off course and need to correct.

Your research domain will often consist of the big question and purpose of your research (what are you wanting to find out?). For example, if I am doing research on AI policy in Higher Education, then I might build a pirate map like this:

- What are the policies of other liberal arts/humanities based colleges?

- How have policies evolved since Fall 2022?

- What has been the impact or effectiveness of these policies?

These three questions are still fairly broad. Still, they form a pirate map that tells me the landmarks that I need to pay attention to in my research: (1) policies of liberal arts/humanities colleges; (2) articles written after fall 2022; (3) articles that primarily evaluate or assess policy effectiveness. If I find myself reading articles or asking questions outside of this domain, then I need to course correct.

Step 2: Chart the Territory

Once we have a general idea of where we are going (purpose) and the landmarks we are looking for (big questions), we need to chart the territory by identifying key themes, variables, or potential gaps in existing literature.

With the key landmarks in mind, we will need to do an initial search and make observations along the way. Try to get into the habit of collecting the research questions that others are asking about your topic. This is usually one of the first things I look for when reading an article or chapter. The research questions I observe from other literature will not only help me read more closely, but it will also help me craft my own questions along the way. You also want to pay attention to the methods that authors use when pursuing the answers to these questions (more on this below).

Here I offer three suggestions for where you might look for some of this background information:

- Popular News/Media: These are some of the most helpful resources for getting the pulse on an issue or topic. Popular media can tell us a lot about the general perception of something and provide us with some of the contextual relevance we might need to strengthen our argument. These sources should mainly be limited to setting the context and illustrating points. Popular media (typically) should not be used to support the main points of our arguments.

- Personal Experience: In a similar way, personal experience is generally not recommended to strengthen our arguments (i.e. hasty generalization). But we can use personal experience to help us understand why we are interested in the research.

- Existing Literature: Most of the time when we engage in research, we will be consulting the existing literature on a topic. These are published (often peer-reviewed) scholarly articles, books, chapters, presentations, etc.

It is from these common sources that we get a feel for the territory we are working in and can finally move forward with the process of crafting our own research questions. I should also add that the observations we make as we engage with the research is also a source from which we gain further territorial insight.

SIDEBAR: Students often express frustration that they “can’t find anything about (or against) their topic.” However, this is rarely the case. If relevant literature seems unavailable, the issue is likely with the framing of the research question rather than the topic itself. Finding useful sources often requires refining your question, exploring related concepts, and engaging more deeply with existing literature. You will always find what you’re looking for – so long as you ask the right questions.

Step 3: Plan the Route

Here is where we finally arrive at the step of asking our research questions. This is where we go from pirate map to aerial view.

Hopefully, a thorough reading of the literature has equipped us with everything we need to formulate our research questions. J.T. Dillon (1984) identified 17 different kinds of research questions that Alvesson & Sandberg summarize in the following four categories (*whispers 🤫* this reminds me of Aristotle’s four causes):

- Descriptive Questions (what is it?) are aimed at knowledge concerning kind, components, parts, quality, quantity, etc.

- Example: What policies currently regulate the use of AI in academic writing and research at universities?

- Comparative Questions (what is it like, not like?) get at the heart of differences and similarities.

- Example: In what ways do faculty perspectives on AI policy differ in the STEM fields versus the liberal arts and humanities?

- Explanatory Questions (what are its causes and effects?) help us further understand the potential impact or effectiveness of a thing.

- Example: What impact (if any) do strict AI restrictions have on student learning outcomes and academic integrity violations?

- Normative Questions (what is its utility? what should be done?) are all framed around what “should” or “ought” to be done in light of the observations we make. These are difficult questions to answer apart from the previous three.

- Example: What are the ethical principles that should guide AI policy development in higher education?

Now that we have four general categories of questions that we can ask, we need to consider the components that make up a good research question. Here are three qualities that every research question should have:

Good Research Questions are:

- Focused: Our questions need to be specific to a given domain and the big questions we are asking. Further, they need to be restricted to only one kind of category (above), and should only be answerable by one type of observation.

- Exploratory: At the same time, we want to ensure that we are asking questions in which we do not already assume or suppose we have the answers. Again, we are wanting to make observations and assuming we have the answer already puts us in the vulnerable state of bias and blindness.

- Strategic: Lastly, we need to make sure that we are asking questions which tell us exactly what we need to look for (observations) in order to arrive at the answer to the questions. Knowing what kind of observations we need to make will help us know what tool to use in order to source those observations.

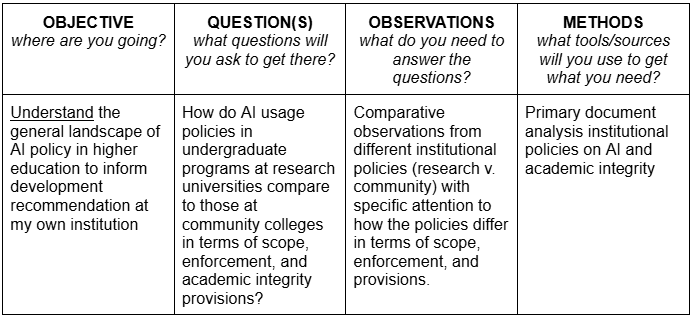

When I am setting up a large research project, I will typically begin with a Research Question Map similar to this (I typically give either each question or objective its own row):

Now that we have a map of where we are going, we are ready to head out on our research journey.

Looking Forward: The View from the Street

Writing research questions and making observations is an iterative process. We are always going back and forth between our research map and the view from the street to make sure we are headed in the right direction. The more observations we make from the street view, the more we might need to refine our research questions.

Often, seeing the details up close can help us get a better understanding of what it is we are looking for.

- Are the questions you asked generating the specific observations you need to advance the purpose or objective of your research?

- Are your research questions actually strategic or do they merely outline the procedure/step to take in your research? Tip: if you use a research question map like the one above, then you should likely avoid this error.

- Can the questions you are asking be answered by the sources/methods you have access to and/or do your sources have access to the information?

Asking and answering these questions when we get stuck along the way will direct us back to the drawing board to refine our questions and ultimately make better observations.

The first step towards improving our observations often starts with asking better questions. This helps us know what to look for.

-

“Observation is where sanity begins.” – Benjamin D. Wright

“You see, but you do not observe.” – Sherlock Holmes

The new Substack Audio feature has been a game changer to me. I am a big fan of podcasts and audiobooks, so having the ability to listen to the writings of my favorite Substack authors while on my morning commute makes the drive through traffic a little more tolerable somedays.

The more I worked on this week’s post, the more I have been bothered by this. No one, including me, goes through the hard work of thinking and writing to then have their words read at 1.5 speed by an artificial voice while navigating through traffic and sipping coffee on the way to work. The cost for this convenience is a form of distraction that takes away from my ability to truly engage the writing.

I spent all of last month thinking and writing about our need to avoid distraction and cultivate attention in our pursuit of excellent thinking. Not only does distraction direct our attention away from the things that matter, it also distorts our ability to make observations and receive the subjects we are studying clearly.

At the bottom of the Cognitive Skill Stack are the twin skills of attention and observation. These two skills form the foundation from which all excellent thinking is built. Admittedly, of the two, the skill of attention is more concrete, practical, and easier to conceptualize. Observation on the other hand is a little bit more abstract. Still, without strong observation skills, our thinking is vulnerable to short sightedness – or, missing the point. In this post, I will outline a basic definition of what I mean by “observation” and address three areas where we often lose sight of this important skill.

What is Observation: The Basics

To begin, observation can be understood as the ability to notice. That might not be very helpful, but stay with me.

We must be clear in our understanding that observation is primarily an act of noticing. It as a distinct act. It is the act of pointing out and calling attention to something, of bringing it front and center.

When we observe, we move information from the background into the foreground. Once it is in the foreground, we can then begin to think with it. For example, we might commit the information to memory, organize it with similar pieces of information, or even utilize it to structure our own arguments and articulation of ideas. But before we do any of that, we must first make observations. While it is in the background, the information is not helpful to us. We need to call it out and bring it to center stage, so that we might then do something with it. A large portion of what it means to cultivate observational skills is found in the focused discipline it takes to not confuse observation with other aspects of our thinking.

What do we notice?

The scope of our observations can be both broad or narrow. It really depends on what we are wanting to notice. For example, when I am reading for leisure I typically have a pretty broad scope in what I might choose to notice and draw out of the text. But rarely do I ever read without an intentional filter. Writing this newsletter at a consistent pace forces me to read with certain key interests in mind.

There are other times when I read and study to make observations about a very specific set of criteria. If I am writing a research paper, I will allow my research questions and the thesis I am pursuing to guide the things I choose to notice and call attention to. In this example, I am not interested in making observations about everything that might stand out to me, but only a very narrow set of criteria that is relevant to the questions I am asking.

Primarily, this is the first step in note taking. We simply mark down the observations we see in the text, hear in the lecture, or notice in our daily lives. Sure, as any good student knows, the observational notes we make must be taken a step further and elaborated on, but we cannot neglect the first step – we need to call attention to something, to give it a place on the page.

Before we can think well, we must first see well. But learning to see takes time and we often lack the patience for it. As such, we are tempted to take shortcuts. We step over dollars to pick up times. We confuse the allure of knowing the forest without understanding the meaning of the trees. For good observation to take place, we need to learn how to slow down and seek again – and again.

Thanks for reading Cognitive Craftsmanship! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.Subscribed

Three Ways We Often Lose Sight

(1) When Expectation Replaces Reality

We mistake our theories, assumptions, or preconceptions for true observation.

In his masterful essay, “The Loss of the Creature,” Walker Percy provides a strong reflection addressing this specific point. Percy calls attention to how our preconceptions (or theories) often prevent us from truly seeing. He describes how travelers who visit the Grand Canyon rarely experience it directly. Instead, they see what they expect to see as it has been designed for them through experience coordinators, postcards, and guidebooks.

The same principle applies to all forms of learning and observation—when we approach something with rigid expectations, we risk losing the reality of the thing itself. Percy describes this as mistaking the theory for the real. We engage our subjects as we expect them to be rather than as they are. As a consequence,, he argues, “the ‘specimen’ is seen as less real than the theory of the specimen.”

The term “specimen” is a helpful clue here that we have made this fatal error in noticing. To borrow Percy’s language, the loss of the true thing has been spoiled from under our very noses.

True observation requires us to strip away assumptions and engage with the subjects we are studying as they are and not as the theory tells us we should assume them to be.

(2) When Interpretation Precedes Perception

We impose meaning too quickly, rather than letting what we observe direct our analysis.

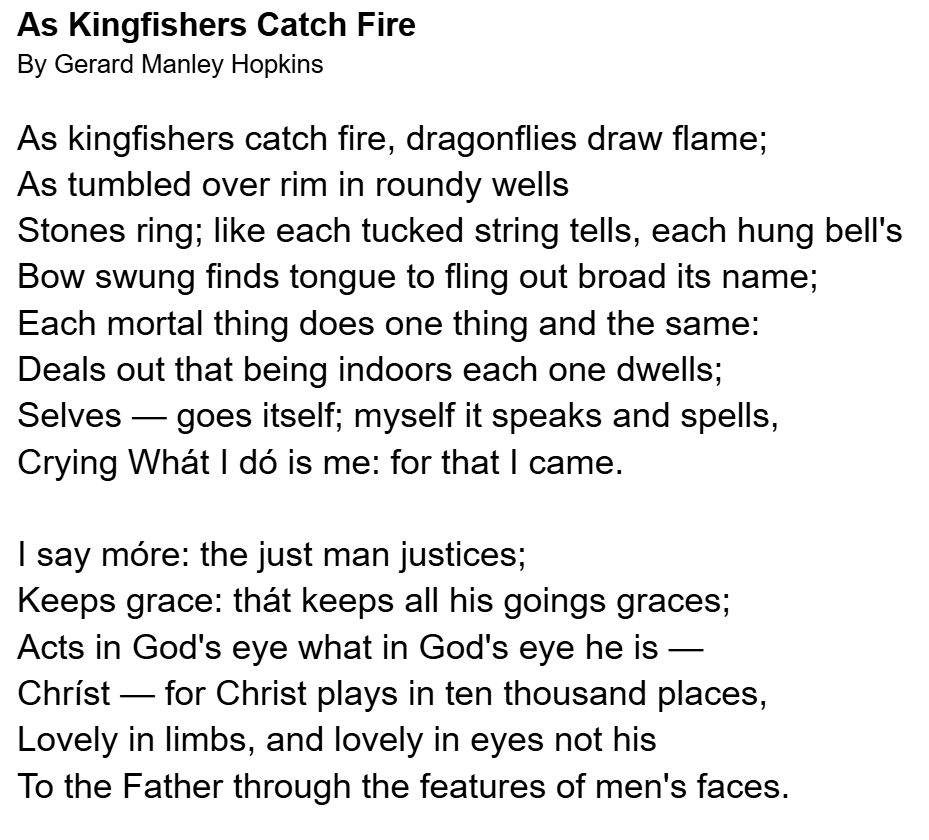

Observation is where sanity begins, because it is grounded in reality (what is there). Antonin Sertillanges in The Intellectual Life further makes this point by connecting the need for a grounding in reality in order to judge rightly. Arguing from Aquinas, he writes, “the real is the ultimate goal of judgment.” If we are going to judge rightly (analysis and interpretation), then we first need to understand the real. Observation is where this happens.

Sertillanges continues, “You as a man of thought must keep in touch with what is; else the mind loses its poise…Thought bases itself on facts as the foot is planted on the ground, as the cripple leans on his crutches.”

It is the observation of the facts of reality that help us keep our heads and steady our minds. The excellent thinker, Sertillanges adds, gathers up the treasure of their observations and from there uses them to “gradually fill out the framework of their thought.”

In her list of “Ten Rules for Students and Teachers,” Sister Corita Kent tells us to avoid creating and analyzing at the same time. “They’re different processes.”

In a similar way, we must avoid observing and analyzing at the same time. They are different processes.

I see students do this a lot when they study history and philosophy. When they encounter a text, they almost immediately want to start analyzing it using their own contemporary frameworks. (“Why are Aristotle’s views on slavery so wrong and offensive – he should know better.”) But without observation, true analysis cannot take place. Through observation, we must first grasp the text as it is before us. (We need to fully understand what it is that Aristotle is saying.)

So seeing clearly and making true observations would require us to pause and notice the particularities of the thing we are studying – its features, parts, structure, “the curious bits” as Percy puts it, before moving on to assign meaning through interpretation and analysis.

(3) When Wanting Shapes What We See

Our desires often dictate what we perceive, rather than allowing ourselves to see things as they are.

All of this seems to culminate (for me at least) in a confusion or misunderstanding of the means and ends. By letting my wants and desires grab hold of the reign in my thinking, I am tempted to skip over the necessary step of observation.

Take the Kingfisher for example.

If I really wanted to know and understand the Kingfisher, I guess I could grab a biology textbook and read pages on its anatomy and skeletal structure. I could read books to understand its flight patterns, behaviours, and the particular ways in which it relates to its environment. But really, all this would do is tell me about the Kingfishers as I should expect to encounter them. If I go out in the wild and encounter one myself, I might miss seeing its real beauty for a living specimen according to the model in the textbook. This would be the mistake of allowing expectation to replace reality.

Or, seeking to understand the Kingfisher, I might go out on a bird watching tour and assess the dynamics of its social life as being somewhat analogous to some other species, or ascribe a moral significance to its color pattern.

These rather silly examples are meant to merely establish a point. That is, in seeking to understand the Kingfisher, I would be doing so through the primacy of my own interpretation – as I understand the bird to be, rather than as the Kingfisher is himself.

In both instances, I would be seeing but not observing.

True observation should give birth to creativity and wonder. When we slow down to observe and notice, the world becomes richer, more intricate, and more meaningful. As Percy puts it, reclaiming our ability to truly see prevents us from becoming passive consumers of experience and expectation.

Looking Forward

My wanting to know and understand the Kingfisher must be done by observing the Kingfisher on his own terms, as I encounter him. In Percy’s words, as one who merely stumbles into the garden of delights and beholds with openness and wonder the thing before them.

To truly encounter the Kingfisher we need the discipline to make observations free from the theories and biases imposed upon us and rediscover what it means to truly behold. Such observations will lead us into deeper and lovelier thinking. The kind of thinking that makes us sing.

-

I love watching master teachers explain their craft. Even if you have no interest in this content, the pedagogy alone is worth your time. Wonderful!

-

If you want to grow in your ability to think and learn more effectively, then strengthening your skill of attention is fundamental. Without strong attentiveness, every other cognitive function becomes compromised. One of the biggest mental challenges we face in this area is the sneaky drift into procrastination.

Procrastination can be understood as intentionally postponing a desired action while knowing the delay will likely have negative consequences. No one is immune to procrastination. We all tend to do it from time to time. But left unchecked and ignored, procrastination can lead to some pretty hurtful consequences – poor grades being the least of these.

By the end of this post you will know more about procrastination, why we do it, and have some science backed strategies to combat the urge to procrastinate when it rears its ugly head.

Understanding Procrastination

One of the biggest misconceptions about procrastination is that it is a result of poor time management. We didn’t manage our time well in the early stages of the activity, so when the deadline came closer we were not as prepared to start which resulted in further delay. I hear this one from student’s a lot, “I just didn’t manage my time well.”

That’s certainly part of it, but it is not the whole equation. In fact, fully understanding procrastination can be quite complicated. In behavioural science, it is actually understood more as a self-regulatory failure which is the breakdown in one’s ability to control or regulate actions, emotions, or thoughts in pursuit of a goal.

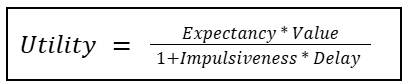

Without being overly complex, procrastination can be understood through a relationship of four variables: expectancy, value, impulsiveness, and delay. These variables form a framework for understanding procrastination known as Temporal Motivation Theory.

Temporal Motivation Theory

Temporal MotivationsTheory (TMT), developed by Piers Steel, is a comprehensive framework that explains human motivation and decision-making, particularly in the context of time-sensitive tasks (which leave us most vulnerable to procrastination). According to TMT, we can understand procrastination through the following formula:

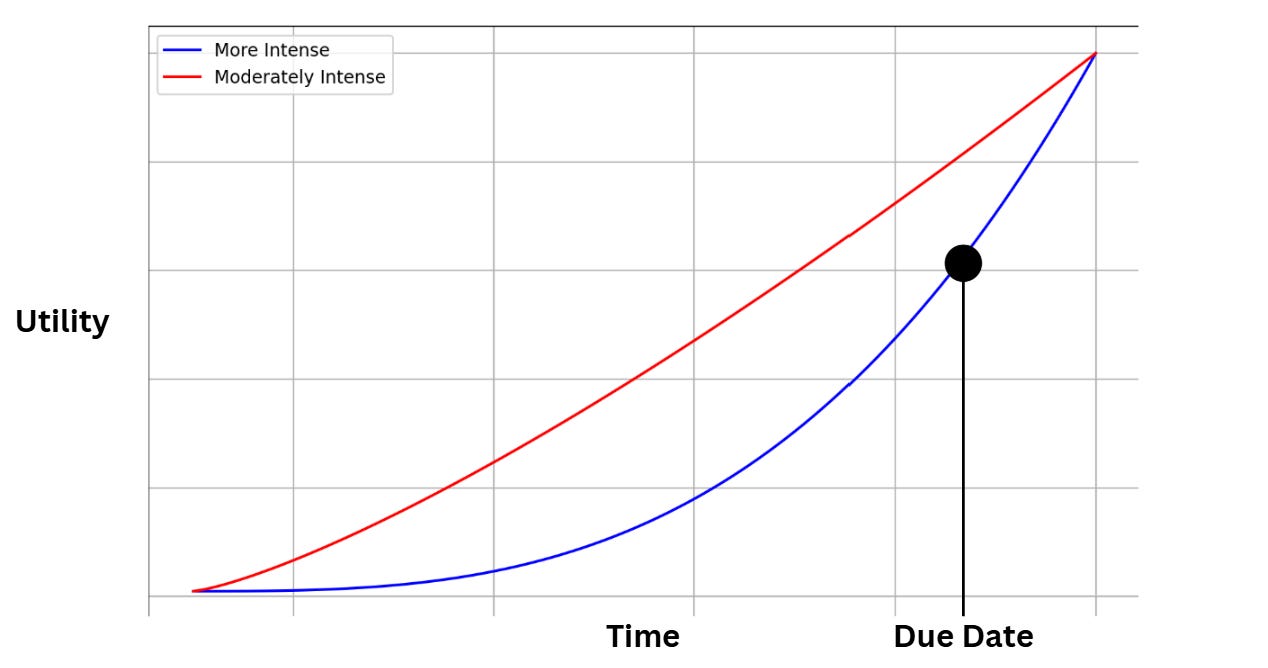

Utility, which is the perceived attractiveness of a task at a given moment and influences motivation to pursue the task tends to increase as it approaches the deadline.

Since delay is always consistently getting smaller, the degree of intensity in which utility increases is determined by the three factors of expectancy, value, and impulsiveness. Essentially, if you are wanting to increase utility and avoid procrastination, TMT suggests that you focus on influencing one or more of these variables.

NOTE: Both lines represent the spectrum of intensity in which we might procrastinate. Utility tends to increase as we approach the deadline of a given task. In TMT, the intensity of the curve is determined by the three variables described below. In this example, the moderate procrastinator (red line) will likely begin working on a task much earlier than the intense procrastinator (blue line). Expectancy refers to the extent in which we believe we will succeed or obtain the rewards of our efforts. We can think of expectancy as our internal probability calculator. Whenever we set out to complete a task, our minds conduct a quick simulation: “Can I actually do this?” The more confident we are in our ability to complete the task, the more likely it is that we will start. This is why (more often than not) past successes result in future action, while failure often leads to paralysis. This is also likely why “fear of failure” is one of the more common reasons individuals with ADHD give for explaining their procrastination.

Value refers to the perceived importance or the significance of the reward we are pursuing for completing the task. As I mentioned elsewhere, procrastination is a value problem. Naturally, we tend to value more immediate and short term rewards than we do long-term ones. This is known more in the economics literature as “time-discounting.” The downside of pursuing growth in thinking and learning is that the payoff is much farther down the road than scrolling through distractions on your phone. Which is why you are probably more likely to turn on the TV at night than pick up a book or study for next month’s exam.

Impulsiveness is the extent in which we act on immediate desires rather than pursue long-term goals. This is also referred to as “sensitivity to delay.” Individuals who are highly sensitive to delay will also tend to act more impulsively. Perhaps the most subtle factor, impulsiveness acts as a multiplier for all other negative influences. It’s the reason we check our phones while studying or scroll social media when we should be writing.

Temporal Motivation Theory suggests that if we want to decrease our urge to procrastinate and increase our motivation for doing the work we need to be doing, then we need to focus on influencing the three factors above. Specifically, we need a set of tools that can help us increase expectancy of success, enhance the value of the activity, and minimize impulsiveness. In the next section, I provide a ten strategies that address each of these areas.

The Procrastination Toolkit

(1) Seek Clarity

One of the easiest ways we can increase our expectancy of success is by seeking clarity. In my experience, procrastination tends to creep up on me when I am confused. Ambiguity is a distraction. It’s aimless. Therefore, if you find yourself putting off a task, it could be that you lack clarity. You might not know what finished looks like. Like being up a creek without a paddle, you need an O.A.R. to get back on track. Specifically, you need to identify clear OUTCOMES (this is what I need to complete), the ACTIONS you need to take to achieve the outcomes, and a plan of REMINDERS (more below) to help you navigate the project or task. If you’re stuck, ask questions and seek clarity.

(2) Make the Task Easier

Another way we can increase our expectancy of success is by making the task easier. For some, the task of writing a research paper is intimidating. You might feel like it’s too big to tackle. Where should you begin? It might feel like you are doomed to fail at the start. Writing a research paper can be a difficult task, but finding and reading eight journal articles is easier. It’s one of the steps in the paper writing process, and one that you can have easy success in. Sometimes we overthink the assignment. Simplify the task, break it down into smaller units, and when in doubt – just start somewhere.

(3) Increase the Value of the Activity

We can also decrease the temptation to procrastinate by increasing the value of the activity. In a previous post, I recommended some ways we could do this through making the task personal, valuable and interesting. As I mentioned in that post, attitude is everything. Research shows that there is a strong relationship between perceived illegitimate tasks (negative attitude) and work procrastination. Negative emotional attitudes have been shown to predict one’s predisposition of procrastination.

(4) Increase the Significance of the Reward

According to Temporal Motivation Theory, high-value tasks with clear rewards are more likely to capture and sustain attention. This means that if you are struggling to pay attention, it could be that you might not have a clear understanding of the reward you are pursuing. Making it personal through something like the C3 reflection framework, is a good first step in this direction.

(5) Decrease the Value of Distractions

I personally find this one to be a very easy tool to use. Scrolling through Instagram or watching YouTube has seldom added any value or significance to my life. They are distractions and waste my time. On the contrary, reading a good book, journaling through my thoughts, studying for my exams, and writing have all added an incredible amount of value to my life both personally and professionally. Often this simple analysis is all the motivation I need to get back on track.

(6) Get Organized

I’ve written previously on the importance of creating a focus environment. The environments we work in have a huge impact on our ability to focus. Research shows that the closer we are in proximity to distractions, the more likely we are to procrastinate. This is one of the easier ways we can overcome procrastination and reduce impulsiveness. Put your phone on silent mode and get it out of the room. Turn off notifications. Find the instrumental music that gets you in the zone. Buy a cool desk lamp. Do whatever it takes to make a fun environment to focus in. Additionally, research has also shown that there is a high correlation between impulsiveness and expectancy of success. The more we work to reduce impulsiveness, the more benefits we might also see in other areas.

Finding this helpful?

Please Consider supporting more of my work.

(7) Keep an Appointment With Your Desk

If you’re one of my previous students, you will recognize this one. I probably say it multiple times a semester – because it’s that important. For most people, we put our most significant tasks on our calendar. If growing in your ability to think and learn is truly important to you, then you need to prioritize it by putting it on your calendar and showing up at a regular time every day or week. This has the benefit of making your focused study time a normal part of your routine which research shows has been noted to reduce the tendency to procrastinate.

(8) Build Good Habits and Stick to a Routine

When it comes to procrastination, building some good habits and sticking to a routine can help in a number of ways. Most notably is the reduction of choices you are faced with on a daily basis. Our ability to resist temptations for distraction are fairly limited. Eventually you get tired of saying “no.” If you are highly impulsive then your capacity to resist distractions might be even more limited. Some good habits and a daily routine can build in some automaticity into your day and reserve some energy in your will power to focus when it really matters.

Related to this, our will power tends to diminish with our energy levels. So, make sleep and nutrition a vital part of your habits and routine to optimize the energy you have available to focus at your desk.

(9) Reduce the Perceived Reward Delay

The further away a deadline is, the less urgency and mental weight it carries. You can always work on it tomorrow. Long deadlines kill urgency and minimize the motivation for pursuing rewards. We can combat this by artificially reducing the perceived reward delay. Implementing something like the Pomodoro Method, or time blocking can be helpful. I’m pretty motivated by coffee and pastries, so often when I complete a big section of a project, I’ll head down to the nearest coffee shop and reward myself. If you are like me, the more you practice these techniques, the more you will experience the benefits of high attentiveness, and the less motivation you will actually need. In other words, keep growing in the Cognitive Skill Stack, and the pursuit of excellent thinking will be the only reward you need.

(10) Focus on Pacing

The stories you’ve heard are true. Slow and steady wins the race. If you are an extreme procrastinator, a focus on your pacing can pay off in the long run. Pacing refers to the timing and frequency in which we engage our work. Most procrastinators tend to cluster their work in batches around deadlines. This is typically what most students mean when they blame their struggles on poor time management. “I didn’t start early enough” might be true, but that’s not the whole story. A focus on pacing means not only starting early, but also showing up often. It’s an obvious fact that the paper you start twelve weeks before the deadline and work on a little bit at a time, will be an objectively better paper than the one you type up the night before it’s due.

Most students also believe that they work better under pressure and are able to produce their best work. This simply isn’t true. It might feel like the writing comes easier and more naturally, but that is most likely a result of motivation that comes with the urgency of the deadline. It is true that there may be a strong correlation between moderate procrastinators and creativity. However, it is not clear whether this is a result of procrastination or the fact that they have spent more time thinking about the tasks prior to the deadline.

When I am working on a research project, I don’t typically start writing until one or two weeks out from the deadline. But my research and planning process is somewhere around two to three hours a week for several months leading up to that point. If you lay a foundation of good research and thinking, the words just flow out of you.

Looking Forward

Procrastination is a challenge we all face, but it doesn’t have to dictate the quality of our work or our personal growth. By understanding the mechanisms behind procrastination—such as expectancy, value, impulsiveness, and delay—you can implement some of the strategies recommended above to help strengthen your focus towards more excellent thinking. Procrastination may feel overwhelming at times, but with the right mindset and tools, you can improve your attention and pursue what matters most. Start now. Your future self will thank you.

-

In a previous post, I discussed the importance of attention and proposed some strategies that might help you strengthen your attentiveness skills. While these strategies are essential for laying the foundation for more excellent thinking, they may not solve all the challenges we face with attentiveness in learning.

As the great Coach Lou Holtz once said, “Ability is what you’re capable of doing…Attitude determines how well you do it.”In the context of thinking and learning, our attitude and approach to learning greatly influences the quality of our attentiveness.

In other words, your struggles with attentiveness might stem from not making a meaningful connection with the topics or material you are trying to learn.

To put it bluntly, you might have an attitude problem.

In this post, I explore the connection between attitude and attention and suggest ways to make more meaningful connections in our intellectual efforts as we pursue more excellent thinking through growth in the Cognitive Skill Stack.

The Connection Between Attitude and Attention

If you’re still with me, I want to clarify what I mean by suggesting that our attention problems might be an attitude problem. We often get defensive when someone implies we don’t care enough about something we are invested in. After all, you’re reading a post about improving your thinking—clearly, you care!

By “attitude problem,” I am simply suggesting that there are some intellectual tasks that we approach with our arms crossed and a pout on our face. There are subjects that we have closed our minds off to and are not open to engagement with. There are activities that we have written off as boring and not worthy of our attention. (All of this is normal by the way – if thinking were easy, everyone would do it.) When these tasks, subjects, or activities inevitably come up, we tend to struggle. Focus becomes more difficult and we get frustrated.

Along with a variety of other reasons, this is why tax season tends to frustrate so many of us. Tax season forces us to think about math and money, and most people tend to have a negative attitude when it comes to these subjects.

As I mentioned elsewhere, focus tends to come more naturally when we care about and enjoy the subject. Conversely, a negative attitude toward a subject makes us lose focus, become frustrated, and procrastinate. However, when we have a positive attitude,whether from prior knowledge or experience, we tend to find it easier to focus and learn.

The best teachers are the ones who inspire and possess the pedagogical gifts that make any subject enjoyable. Similarly, the best students are those who possess the “Creative Imagination,” to find meaningful connections between the less enjoyable subject and the subjects they love.

In the rest of this post, I provide some strategies for making the kind of meaningful connections that promote a positive attitude and therefore greater attentiveness for any subject.Three Strategies for Making Connections that Improve Attention

(1) Make it Personal

Replace “I can’t focus on this” with “I haven’t found why this matters to me yet.”

If our ability to pay attention is positively affected by our personal connection to a subject, then one of the biggest levers we can pull in strengthening our attentiveness is to make more personal connections with the subject.

As I highlighted above, attentiveness is not an effort in forced willpower. Rather, it’s about connecting dots to what matters to you. So, make it personal.

The best learners aren’t those with naturally long attention spans. They’re the ones who actively find ways to make subjects relevant to their interests and goals. Further, the strongest motivators for our work (according to this research) seem to be those which are closely tied to our personal identity.

In other words, the motivation for emotional pleasure or more economic benefits do not seem to be as strong as the motivation that comes from doing something for the sheer purpose of “that’s just the kind of person you are.”

The employee who deeply identifies themselves as someone who loves learning will find it much easier to focus through the training seminar than the one who is just in it for the credential.

Here’s the good news, with practice and intentionality, we can get better at making these connections.

The next time you find yourself struggling to engage with a particular subject, take out a sheet of paper and give this exercise a try:

The C3 Framework for Making it Personal:

Connect: make as many personal connections as possible with the subject. Reflect on your personal interests, daily life, career goals, and calling or broader life purpose

Clarify: Why does this subject or topic matter from a big picture perspective? Why are people interested in studying this? What makes this topic interesting? What questions do I need clarity on to find it more interesting?

Customize: How can you customize your engagement with this topic? Maybe you have a lot of unanswered questions? Maybe step two was really difficult for you – Good! That means you have a lot more to learn.There are no boring subjects, just subjects you haven’t made a personal connection with yet. It’s difficult work, but making a difficult or seemingly boring subject more personal can dramatically help you feel more connected and therefore more attentive.

(2) Make it Valuable

Replace “this is not worth my time” with “how can I prioritize this more?”

No one is immune to the habit of procrastination. We all do it. Some of you will do it later…😀

Jokes aside, procrastination is one of the biggest intellectual struggles we tend to face. I know that is certainly true for me. I think a lot of it has to do with the fact that it seems so mysterious – we have a difficult time understanding why we procrastinate.

Everything changed for me, when I started viewing procrastination as a value problem. In other words, I tend to procrastinate, because I value the distraction more than the activity I really ought to be doing.

In the realm of thinking and learning there are a variety of explanations for why we tend to undervalue certain subjects or activities. Perhaps most notably is the reward delay that we experience in these areas.

For example, the enjoyment I get from watching my favorite show or spending time with friends is immediate, while the enjoyment I get from finally “cracking the code” to some complex statistical model is delayed for days, months, or sometimes even years.

If I am the kind of person who is wired to seek immediate gratification, then I will likely be tempted to procrastinate more, since I would tend to value immediate pleasure over the delayed reward of learning.

Making a subject or intellectual activity more valuable will help you avoid the distractions and commit your focus towards higher value activities such as thinking and learning. To do this we can do things to reduce the reward delay by breaking things down into smaller units and rewarding ourselves at each milestone. Or, we might make it personal (above) and try to understand why it matters to you and your long term goals.

(3) Make it Interesting

Replace “this is boring” with “how can I make this more interesting?”

When we learn to put it in its proper place, boredom is not necessarily a bad thing. Boredom is a sign that we are not as engaged with the material we are seeking to learn as we should be. It is an alarm bell that, if we are attentive to, will help us improve our thinking.

Here’s what I mean. The best response to boredom is not avoidance, “how can I do something more interesting.” Rather, it is to dig in our heels and seek out ways to make it more interesting.

So brainstorm. What would it take for the subject to be more interesting? What do you want to know? What questions do you have? What are its connections to the other topics you are interested in?

The best thinkers are the ones who can make the most connections with the subjects they are trying to learn. It’s difficult work, but well worth the effort! The key is being aware of what is happening when we get bored, and recognizing boredom as a sign that we are not engaged and need to change our approach.

Looking Forward

Attention is not just about willpower—it’s about attitude. By shifting our mindset and making it more personal, valuable, and interesting, we can enhance our attentiveness and overall learning experience. Remember, the journey to excellent thinking is ongoing. As we grow in our development through the Cognitive Skill Stack, embrace the process, stay curious, and commit to putting some of these ideas into practice. With time and effort, you’ll find that even the most challenging subjects can become opportunities for growth.

-

I had to put my phone down to write this entry – seriously. Paying attention is difficult.

This has always been true. In my research on the history of learning and thinking, I am always surprised to find intellectuals from centuries past who struggle with procrastination and distraction. Our ability to apply our sustained attention to a chosen task or stimuli is part of what makes us human. On the flip side, it seems like our struggle to do this very thing is also a part of what makes us human.

In the pursuit of excellent thinking, honing the skill of attention is foundational. Without it, every other cognitive function becomes compromised. The good news? Attention is trainable, like a muscle. In this post, I expand on the importance of this first skill in our Cognitive Skill Stack and discuss some of the ways I have worked on improving in this area. Hopefully, you find them beneficial as well.

Why Attention Matters

Attention is the cognitive ability to concentrate on specific stimuli or tasks for a sustained amount of time while ignoring distractions. Like a flashlight in a dark room, attention illuminates what matters while keeping the peripheral noise in shadow.

I have the privilege of teaching, working with, and working around college students. With first hand experience, I can assure you that the skill of maintaining focus in a lecture, on homework, in the middle of a conversation over coffee – is rare. But it’s not just college students. Research shows that the average knowledge worker is interrupted every 11 minutes and requires somewhere around 23 minutes to return to deep focus.

It seems that there are two obvious problems that need to be addressed: (1) The frequency of interruptions – you have some control over this, but I’ve worked in enough different office environments to know that this is not always possible; (2) The amount of time it takes to return to focus – this is where the skill of attention comes into play. Distractions, boredom, and procrastination are inevitable. The real question is, how can we reduce the time it takes to go from distraction back to engaged focus?

Attention is the gateway to all cognitive processes. Without the ability to focus, our minds are scattered, our productivity suffers, decision-making loses precision, creativity diminishes, and learning efficiency decreases. Without a strong ability to focus, other skills like memory and logical reasoning cannot function effectively. Developing attention and focus is not just about avoiding distractions; it’s about training your mind to sustain effort on meaningful tasks.

In an age of seemingly endless distractions, the ability to focus has become one of our most valuable cognitive resources. As with all important skills, developing a strong ability to focus is challenging. But here’s the exciting part: attention is not a fixed trait—it’s a trainable skill that responds to consistent practice, much like building muscle in the gym. Everyone can improve their ability to pay attention. Here are four strategies that have worked in my life.

Four Strategies for Improving Attention

Just like other skills worth pursuing, the price for paying attention is costly – but worth it. The methods I list below are not quick and superficial fixes. Attentive thinking is slow, and that’s a good thing. Below are some of the daily habits I have sought to cultivate that over time have greatly improved my ability to lock in and focus my thinking.

(1) Create a Focus Routine and Environment

Being the creatures of habit that we are, one of the easier ways we can improve our attention is by developing a thinking routine that helps us signal to our brain when it is time to focus. An initial draft of this post was written in the early mornings after following this routine:

- 30 minute walk on the treadmill & listening to the Bible

- Praying a Psalm

- Brewing a cup of coffee

- Sharpening 2 Blackwing pencils

- Opening my thinking notebook to begin a focus session

Specifically, the routines of prayer, coffee, and pencils (it’s weird – I know) seem to be the signals needed to help me get started. My study/school routine and pre-work routine in the office at the start and middle of the day follows a similar pattern.

It doesn’t matter what the specifics of your routine are as long as you have one. If you don’t know where to start, just start small with elements you know are helpful. Make notes, and adapt as you go. For example, walking has been a new development and improvement for me lately while prayer and coffee have been consistent staples.

Setting up your focus environment can also be a component of your routine. I think a lot of people overthink this one (or, at least I do). Your focus environment doesn’t have to be absolutely perfect, organized, and distraction free. It just has to be the place where you do your most important and attentive work. Your focus environment should not be multifunctional. Its singular task is providing you with a space to sit down and focus. It’s a refuge from distraction.

As you strengthen your attention muscle, you will become more adaptable and less dependent on your routine and environment. I am at a point now where I can turn on “focus mode” pretty much anywhere. Having a routine that is not context dependent will help with this down the road. Whenever I am having trouble focusing, I start with the basics. I clean my room first, and then get to work on the other areas.

(2) Intentional Sets and Reps

For most of my life, I’ve been pretty strong. For a short period of my life, I was really strong. However, due to some injuries and negligence, until this past year I had never been able to perform more than a single pull up. What changed? I applied some attention to the exercise.

I begin with simply hanging from the bar. When that became easier I incorporated some assisted pull ups with a slow unassisted descent. To really focus on the exercise, I added a few sets of pull ups to every workout. As time progressed, the pull ups became easier, and I started performing multiple reps without any assistance. Intentional focus pays off.

If you want to strengthen your attention muscles, you need to apply some intentional sets and reps periodically throughout the day and week. For those who are unfamiliar with the terminology. A “rep” is short for repetition, the singular act of performing a movement in an exercise. A “set” is the number of times you repeat that grouping of repetitions. So, 2 sets of 5 pull ups would be five pull ups, performed three times with some rest in between the sets. Stay with me.

Implementing something like the Pomodoro Method into your day can be an effective way to apply this technique. The method is relatively simple:

- Pick a task you want to focus on

- Set a timer for 25 minutes (this is called a “Pomodoro”)

- Work on the task until the timer rings

- Take a short break (about 5 minutes)

- After four Pomodoros, take a longer break (15-30 minutes)

So after 1 set of 4 Pomodoros, you would have worked with distraction free focus for close to two hours. The first time you sit down to do this, you might struggle. That’s okay. I remember when I first applied this method. I could barely make it through 2 Pomodoros. As with strength building, the same concepts apply here. Intense focus, followed by intentional recovery, should result in improved ability.

Unless I am really struggling with distraction or working on a major project, I rarely set a timer anymore. But this is generally how my work rhythm is structured.

The early morning is where I try to do some of my most focused creative work. Here, I don’t set a timer, but instead use the John Steinbeck method of sharpening two Blackwing pencils (instead of 24), and writing until they are sufficiently dull.

(3) Focused Play

Because we are thinking about attention as a muscle, it is important to point out that some forms of focused play can be beneficial for strengthening our attention muscles. It doesn’t really seem to matter a whole lot what you focus on, as long as you are focused for extended periods of time.

That being said, since we tend to have an easier time paying attention to the things we enjoy the most, the attention gains we experience from an activity like playing video games are likely extremely minimal. If the activity is enjoyable, it won’t produce enough of a challenge to stimulate growth in your ability to focus. When it comes to focused play, the idea is to find an activity that is enjoyable yet demanding on your attention.

I enjoy lifting weights as a form of focused play. It provided the benefit to both my physical and intellectual health. Having a lot of muscle mass seems to be a strong indicator of long term general and cognitive health. An added benefit of picking up heavy objects throughout the week is improved attention. For a variety of safety concerns, it’s not recommended to let your mind wander while handling heavy weight. You have to have all your attention on the activity and mechanics of your movement.

In addition to physical exercise, other forms of focused play might include: puzzles, brain games, writing poetry, challenging board games, playing an instrument, building blocks like Legos (or, Magna-Tiles for toddler parents), arts and crafts, and reading a challenging book.

(4) Prayer and Meditation

The French philosopher Simone Weil, once summarized the whole enterprise of Christian education as an effort in cultivating the attention necessary for prayer directed with affection for God. Her entire essay (linked above) is absolute gold and well worth your time.

Even if you would not consider yourself religious, Weil’s point is worth consideration. There are some exercises, like reading or puzzles, which train lower forms of attention which will aid us in the pursuit of higher attentiveness through prayer and meditation. Interestingly, Plato lays out a similar argument in The Republic when he discusses the importance of mathematics. To summarize, mathematics is an exercise in preparing the soul for the contemplation of reality (the art of Philosophy).

Following the line of thinking from Weil and Plato, I want to propose that the attention muscles we build through the three strategies above find their greatest pay off in our engagement with exercises that require higher forms of attention such as prayer, meditation, the pursuit and contemplation of the truth,etc. At the same time, due to the level of attentiveness they demand, these higher forms of attention also help us sharpen and strengthen the lower forms of attention.

As I mentioned earlier, I like to spend my early mornings in focused prayer (usually with a Psalm) and meditation on Holy Scripture. When it comes to meditation, I typically use a combination of making observations, reflection, and committing the passage to memory. Most mornings I record my thoughts by pencil in a notebook.

Looking Forward

The skill of attention forms the foundation for the pursuit of excellent thinking. By strengthening our attention muscles, we can enhance our ability to learn, solve problems, and achieve our goals. The fact that attention is trainable offers hope and opportunity for anyone seeking to improve their cognitive fitness. In an age of constant distractions, the skill of focus is more valuable than ever. By investing time in practices that enhance attention, we can unlock your full cognitive potential and achieve greater excellence in our thinking as we progress through the Cognitive Skill Stack.

-

In 2024, I worked on several research projects exploring critical thinking, logical reasoning, intellectual virtue, and the aims of liberal arts education. I learned a great deal over the past year. Most importantly, I strengthened my conviction that the ability to think deeply and meaningfully is an art. It requires consistent effort, but like any craft, it holds immense value. If thinking deeply is an art, then it involves certain skills that can be developed and refined over time. Just as a painter improves their brushstroke or a carpenter perfects their detailing, our minds can enhance specific cognitive skills for sharper and more thoughtful intellectual work.

As we head into 2025, I want to introduce a concept I call “The Cognitive Skill Stack.” This is a set of seven skills that provide a framework for improving our thinking abilities. While technological advancements might make some aspects of thinking appear easier, the reality is more complex.

Technology often simplifies superficial thinking. However, true thinking—the kind that matters—is never easy. While technological tools provide greater access to information, this is only the first step. Just as access to gold ore doesn’t eliminate the need for refining it, access to information doesn’t replace the effort of deep, meaningful thought.

The Cognitive Skill Stack forms the foundation for processing information, solving problems, and generating new ideas. Below is a summary of each skill, its definition, importance, and tips for improvement, presented in ascending order of difficulty.

Note: I’ll expand on each of these in future posts.

(1) Attention

At the foundation level of the cognitive skill stack is the skill of attention. We can understand attention as the ability to concentrate on specific stimuli or tasks for a sustained amount of time while ignoring distractions.

We are constantly bombarded with distractions to lure us away from deep engagement with thought. Once distractions do occur, it takes us a significant amount of time to refocus our attention back to the tasks at hand.

Honing the skill of attention is an essential fundamental skill to excellent thinking. Without it, every other cognitive function becomes compromised. The good news? Attention is trainable, like a muscle.

To strengthen your skills of attention, work on intentional periods of deep engagement followed by brief periods of intentional rest and recovery. The more intense and challenging the stimuli, the more rest and recovery you will need. I’ll share some more tips in future posts, but for now something like the Pomodoro Technique is a great place to start.

(2) Observation

A little less obvious than the skill of attention, but equally as foundational is the skill of observation. This can be understood as the ability to notice key details, patterns, similarities and differences, etc.

Our contemporary culture tends to value faced paced thinking. We often feel pressured to make decisions in a hurry, based on our initial impressions of the details – without necessarily having the full picture. Therefore, the skill of making observations, to look and look again, is essential for clear and thorough thinking.

One initial step in strengthening your observation skills is to challenge yourself to exhaust your noticing. Pick a subject, look, make observations – rinse and repeat.

(3) Memory

I learned about the importance of this skill later in my intellectual development. When we discuss memory, you likely have (traumatic) flashbacks to index cards and mindless repetition of facts, dates, and formulas. Memory is the ability to learn, store, and retrieve information when needed.

Modern technology makes it easy for us to offload (or upload) our memory to external tools. This is a good thing when it comes to certain information like my task manager, calendar appointments, and digital files. But it is not an adequate tool for the full possession of knowledge. When we memorize information, it becomes a part and extension of us in ways that digital tools fall short of. For example, if you have read and memorized parts and passages of the Christian Bible, your ability to engage with literature is significantly enhanced. You pick up on things others cannot. Your observations are sharper. You can more naturally interact with the material. Sure, you can always look it up, but without a well of memory to draw from you are limited to the observations of others and have to take their word for it.

I was reminded of the importance of memory recently after a re-read of Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451. The full possession of knowledge through memory should be enough motivation to pursue growth in this liberating skill.

(4) Taxonomy

One of my favorite metaphors to use when thinking about mental activity comes from the Yale College faculty report of 1828 (hang with me). We can think of a mind like a house, they write, and one of the outcomes of strong mental powers is that of a well furnished and organized mind. The skill of taxonomy (association and organization) captures this idea of the well furnished mind. We can think of this skill as the ability to group, classify, and organize information. It is the skill of knowing which piece of “intellectual furniture” belongs in a given room and how it relates to the other pieces of furniture. Organized information is easier to retrieve and apply. As Seth Godin, recently pointed out, taxonomy is a service both to ourselves and others. This skill is the bridge between knowledge acquisition and practical application.

The skill of association and organization works hand in hand with the skill of memorization. As we expand our memory vault, the increased volume of data we now possess allows us to make better connections. Again, this is where our digital tools are not so helpful. To exercise this power, you actually have to think and retrieve information. You have to know where to look and how to put the pieces together. This is probably the most abstract skill in the list. I’ll come back and expand on this idea in future posts.

(5) Logical Reasoning

The skill of logical reasoning is probably the first place our mind goes when we think of skills to improve our thinking. It certainly is an important skill, but without the previous four, improving our ability to reason logically can be a struggle. Logical reasoning enables you to construct strong arguments, avoid cognitive biases, and solve complex problems effectively.

One of the most helpful places to start building this skill is simply learning the structure of strong argumentation and the simple fallacies that make for weak arguments. By learning the basic structure of argumentation, my ability to understand, summarize, and communicate complex ideas has greatly improved.

(6) Wisdom (or, Judgment)

It is not enough to know how to make strong arguments that withstand attack. We must know how to implement the mental powers at the proper time, in the proper way, and with excellent intellectual character. In other words, we need the virtue of wisdom to govern our thinking. Wisdom is the hallmark of mature thinking.

Growing in wisdom is never easy, but a good place to start is by seeking feedback. Asking for feedback from someone who’s opinion and counsel you trust takes a whole suite of virtues like honesty, humility, courage, etc. The activity of reflection helps you to learn from your mistakes and successes. Applying the feedback and advice you receive further deepens the channel of wisdom making it more enjoyable and natural as you progress in this intellectual virtue. To summarize King Solomon the author of Proverbs, wisdom is costly – but it’s worth it.

(7) Creative Imagination

The last skill on the list is the human superpower of creative imagination. This is the ability to generate new ideas, synthesize information, and develop novel solutions to problems. Creative imagination is distinct from association and organization in the sense that it unites the entire economy of the mind. Rather than developing ideas out of a single room, creative imagination integrates the whole mental house. It integrates subjects and concepts in order to arrive at new ideas and creative solutions.

Looking Forward

My goal as I head into 2025, is to apply myself to learning and expanding more on each of the skills in this framework. This might be a controversial take to end a post on, but as technology (A.I.) develops to take on more basic cognitive tasks, the human advantage will lie in higher-order thinking—exactly what the Cognitive Skill Stack is aimed at. By mastering these skills, you’re not just improving your thinking; you’re future-proofing your mind.

What level of the cognitive skill stack are you working on right now?

Let me know your thoughts!

-

I came across this short opinion essay in a 1919 edition of The Journal of Education. Consider this yet another entry into the “persistent challenges” folder:

CREDITS AND EDUCATION (F.B. Pearson)

If ever we come to place more emphasis upon credits than upon education it will be a sorry day for our institutions. Credits are but the label, while education is the contents of the package. We shall not get much nourishment if we devote our main attention to the label.

The office of the registrar has its use, of course, but it is not the power-plant of the institution whatever the students may think of it. A college student was copying statistics to exchange for credits, but growing weary and being resourceful he hired a girl at fifteen cents an hour to do the copying for him while he went off to the ball game. The college gave him credit for research work not knowing that his research-ing was done from the bleachers at the ballpark.

The college sometimes inveighs against the fractional credits that are brought to them by graduates of the high school, not realizing, apparently, that the teachers in the high school are graduates from the college and learned the trick of credits there. They wanted to fit out David with artificial trappings, but he put them aside and went forth with his own trained powers and slew Goliath.

Socrates and Agassiz were accounted great teachers, but if they ever said anything about marks and credits it is not a matter of record. Colleges, normal schools and high schools combined cannot build an elevator that will carry their students to the top of Mt. Parnassus. Climbing is the only mode of travel. These institutions have to do with civilization and human destiny and these cannot be measured in fractional percentages. They are dealing in eternal futures and such things cannot be estimated with calipers. We shall do well to keep our attention fixed upon the contents of the package and not the label. Let’s teach school.

Source: Pearson, F.B. “Credits and Education.” The Journal of Education 90, no. 22 (2258) (1919): 613–613. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4276

-

I’ve been working through Sir Arthur Clutton-Brock’s The Ultimate Belief (New York, 1916). This quote from the first chapter is gold:

To them philosophical questions are all open questions; and they believe that this is so because of the failure of philosophy to prove anything. But it is not philosophy that has failed; rather it is men who have failed to do that by which alone they can be convinced. Philosophy is a science, and its truths can only be confirmed by experiment. But, whereas to confirm a truth of botany it is necessary only to make experiments upon plants, to confirm a truth of philosophy we must make experiments upon ourselves. Thus, if philosophy tells us what we ought to value, we can only test the truth of it by valuing that which it tells us to value. We must make an experiment in valuing; and we must make it in action as well as in thought or feeling. If, for instance, a man values money more than anything else, he will act in accordance with his values; his one object in life will be to get money. So, when philosophy tells him that there are other things more valuable than money, he must alter his whole way of living, if he is to test the truth of that philosophy by experiment; and this he will often refuse to do.

I’ve been exploring the concept of evaluative thinking as a potential bridge between intellectual virtues and critical thinking. Evaluative thinking encompasses components of critical thinking such as reasoning, analysis, and evaluation, but it extends further to include valuing and making judgments. To excel in this, we need to be anchored in certain virtues and universal principles that guide our thinking. Without this grounding, we risk making temporary value decisions based on the urgency of the present, a dangerous temptation.

The quote above illustrates this point well. If we aim to foster a love of learning and virtue, we must teach what it means to possess these intellectual character qualities—and we do so by helping individuals put these values into practice.

Teaching students that valuing epistemic goods such as truth, wisdom, and understanding is a worthwhile pursuit that also involves imparting the intellectual character traits necessary for this task. The difficulty with this is that it challenges our modern sensibilities and time preferences for immediate reward. The payoff of intellectual character takes time, the virtues of humility, patience, and courage. We are often tempted to run away from these universal goods towards temporary solutions that are less comprehensive and fulfilling. We have a hard time sticking around for an answer.

Clutton-Brock continues:

That is why certain truths of philosophy, though they may have been confirmed by experiment in the lives of all good and wise men, are not universally accepted. There is a philosophy which might say of itself:

“To this end was I born, and for this cause came I into the world, that I should bear witness unto the truth. Everyone that is of the truth heareth my voice.” (John 18:37)

We know what answer Pilate made to these words.

He asked: “What is truth?” (John 18:38), as Bacon says, would not stay for an answer.

If he had listened to the answer and believed it, he would have been forced to alter his whole way of life. Rather than do that he believed that truth was not to be found. But truth remains truth, even though men ask what it is and will not stay for an answer; and to those who hear it and act upon it it proves itself to be truth.To nurture a love of learning and to echo the Teacher, “Get wisdom, and whatever you get, get insight” (Proverbs 4:7), requires the kind of intellectual character that possesses the resolve to stick around for an answer.

-

I was cleaning out a research folder and came across the following quote. I’m not sure where I came across it, but I’m intrigued and plan on reading the original source in it’s entirety.

Education ought to teach us how to be in love always and what to be in love with. The great things of history have been done by the great lovers, by the saints and men of science and artists; and the problem of civilization is to give every man a chance of being a saint, a man of

science, or an artist. But this problem cannot be attempted, much less solved, unless men desire to be saints, men of science, and artists, and if they are to desire that continuously and consciously, they must be taught what it means to be these things. [Sir Arthur Clutton-Brock,

The Ultimate Belief (New York, 1916)] -

Jesse Stuart (1906-1984) has a wonderful essay that calls for an examination of character. In the days ahead, are you going to be a builder or a destroyer? What kind of students are you going to leave the world?

Now weigh yourself. See if you expect to take and not give, or if you expect to give more than you take, to build instead of destroy. Weigh yourself, and if you want to leave the world better because you have lived, you are a constructionist. If you see yourself at the head of a marching army, obliterating people, applying the scorched earth policy to helpless people, obliterating those you dislike for the thrill of it, supervising a slave labor camp or approving of one, then you are a destructionist. The man who drives out of his course to hit a dog or smash a terrapin on the highway or shoots down posters around a game preserve is another. Now weigh yourself carefully Which one are you? Which side will you be on in the crucial years ahead?

Here is another summary of Stuart’s philosophy:

Do you know what my philosophy is? It’s to build and not to destroy. You build and you have to keep building. You can’t turn around and start destroying. I figure there are two kinds of people in the world today: the constructionists and the destructionists. They’re not Democrat or Republican or Catholic or Protestant; they’re just those two categories and that’s all. When the world gets to the place where the destructionists outnumber the constructionists, you’ve the Roman Empire all over again when she vanished. Look at the airplane hijackers. Look at the problems on campus, damaging and destroying. Look at the fellows who blew up those planes in the Middle East. But I think the world is waking up to that destructive stuff. Society has to wake up to it if society wants to live. Everybody is too involved in sweetness light. They don’t want to upset people with the truth. and say sweetness doesn’t always bring light. You have to take a stand and get involved. Even if you get hurt, and oh, listen, they can hurt you out there.

Dick Perry, Reflections of Jesse Stuart: On a Land of Many Moods (NY: McGraw Hill, 1971). -

I was reading Herman Bavinck’s book Christianity and Science this morning, and this quotation about the limits of scientific inquiry really struck me.

According to Bavinck, scientific inquiry is useful for understanding and investigating the natural world, but it cannot account for or help us make sense of our metaphysical needs and spiritual longings.

The question is, rather, why our capacity for knowing is equipped in such a strange way that we absolutely cannot know the things we would most want to know. After all, seeking the truth is no sin, and the truth is no lesser good than holiness and glory. Still, to say more, one can draw such borders, but nobody holds to them. Each person has his own [metaphysical need].

What we seek and need for our life is a worldview that satisfies both our understanding and our inner life. Such a worldview is built up not from details about visible nature alone but just as much from elements provided for us by our inner experience; it must bring unity in all our knowing and acting, bring reconciliation between both our believing and our knowing, and make peace between our head and our heart. We believe in that peace and seek it, because the truth cannot fight against itself, because our mind is one, because the world is one, because God is one!

Even if the ideal is so far removed from us, the end goal of science can be none other than the knowledge of the truth, of the full pure truth. That knowledge is never, and shall never be, a comprehending of how the human being should be able to find the Almighty fully. Rather, knowledge is something different from and higher than comprehending; it does not exclude mystery or chase away adoration. Alongside knowing, worship increases, because all science is the translation of the thoughts that God has laid down in his works. Pseudoscience can lead away from him, [but] true science leads back to him. In him alone, who is the truth itself, do we find rest, as much for our understanding as for our heart.

How can one read this last paragraph and not be immediately reminded of the opening lines in Augustine’s confessions:

Great art thou, O’ Lord, and greatly to be praised; great is thy power, and thy wisdom is infinite. And man wants to praise you, man who is only a small portion of what you have created and who goes about carrying with him his own mortality, the evidence of his own sin and evidence that Thou resists the proud. Yet still man, this small portion of creation, wants to praise you. You stimulate him to take pleasure in praising you, because you have made us for yourself, and our hearts are restless until they can find peace in you.

-

I really like this quote from Moss et al. on the meaning of “well done” qualitative educational research:

For qualitative research, well done means the study involved a substantial amount of time in fieldwork; careful, repeated sifting through information sources that were collected to identify “data” from them; careful, repeated analysis of data to identify patterns in them (using what some call analytic induction); and clear reporting on how the study was done and how conclusions followed from evidence. For qualitative work, reporting means narrative reporting that shows not only things that happened in the setting and the meanings of those happenings to participants, but the relative frequency of occurrence of those happenings—so that the reader gets to see rich details and also the broad patterns within which the details fit. The reader comes away both tree-wise and forest-wise—not tree-wise and forest- foolish, or vice versa.

When I say a study has an educational imagination, I mean it addresses issues of curriculum, pedagogy, and school organization in ways that shed light on—not prove but rather illuminate, make us smarter about—the limits and possibilities for what practicing educators might do in making school happen on a daily basis. Such a study also sheds light on which aims of schooling are worth trying to achieve in the first place—it has a critical vision of ends as well as of means toward ends. Educational imagination involves asking research questions that go beyond utilitarian matters of efficiency and effectiveness, as in the discourse of new public management…, especially going beyond matters of short-term “effects” that are easily and cheaply measured. (p. 504)

-